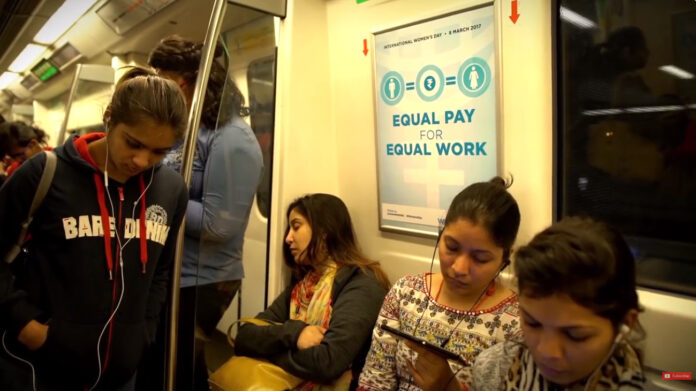

Four new labour codes implemented by government starting 25 November is a mixed bad for working women and professions and workforce across India. In the end result this actually hits working women’s assured participation in the growing economy.

For women, the labour codes have two faces. On one side, the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code allows women to work night shifts subject to safety measures. This expands job opportunities in manufacturing, IT, retail and services that operate round the clock. Provisions on crèches and maternity benefits have been retained or strengthened within the consolidated framework, which may further support women’s participation in the formal economy.

But concerns remain. Increased flexibility for employers to hire and fire could disproportionately affect women, who already face higher attrition risk due to marriage, maternity or caregiving responsibilities. If companies opt for fixed-term or short-term contracts to avoid long-term obligations, women may find themselves in more precarious employment. The fear is that the codes, while offering new openings, may also reduce stability unless enforcement and monitoring are robust.

The Government of India’s ambitious labour law overhaul rests on four new labour codes: the Code on Wages, the Industrial Relations Code, the Code on Social Security and the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code. Together, these codes replace 29 outdated and irrelevant laws and aim to modernise India’s labour market with a unified, simpler regulatory structure. The codes promise easier compliance through common definitions and standardised rules. For the government, this is a long-pending rationalisation meant to support formalisation and investment.

Yet, public response has been of vast dissatisfaction. Employees, trade unions and worker groups see the new structure as tilting the balance of power towards employers. Companies and industry bodies argue that the reforms are essential for boosting competitiveness and accelerating job creation. The polarisation has kept implementation on hold even though all four codes have been passed by Parliament.

Why Workers and Unions Are Opposing the Codes

The strongest criticism comes from the Industrial Relations Code, which raises the threshold for mandatory government approval for layoffs and retrenchment from 100 to 300 workers. Unions say this gives companies too much freedom to fire staff and will lead to job insecurity across manufacturing and services. Many also object to tighter rules on strikes. Notice periods before a strike, along with conditions that bar strikes during ongoing proceedings, are viewed as restrictions that dilute workers’ bargaining power.

Another flashpoint is the proposed change in wage structure. The codes require that at least 50 percent of total compensation must be counted as basic wage. Employers may prefer this because it standardises calculation, but workers fear that higher mandatory PF contributions will reduce take-home salary at a time when inflation has already tightened household budgets.

The codes also centralise many regulatory powers, cutting down on state-level variations. For unions, this threatens flexibility in dealing with local labour issues. They argue that the new framework prioritises investment friendliness over employment stability and worker protection.

What Has Changed from the Past

Under the older system, labour laws were numerous, fragmented and often outdated. Definitions varied from law to law, enforcement was uneven across states and compliance was a nightmare for both small firms and large manufacturing units. The new codes attempt to unify these definitions, digitalise compliance and bring casual workers, platform workers and unorganised labour under some form of social security coverage. This is one of the major structural changes, as India had no formal mechanism earlier to include the casual workforce.

The government also wants to push fixed-term employment as a mainstream practice. This was previously limited and poorly defined, forcing industries into contract or informal hiring. The new framework formalises it. Worker organisations, however, see this as shrinking the space for permanent jobs.

Pros and Cons of the Labour Codes

For industry, the biggest positive is predictability. The codes encourage easier hiring and firing, standardise wage definitions and reduce inspections through digital self-certification. This, companies argue, will improve India’s global manufacturing competitiveness and attract investment away from nations with rising labour costs. Many in the corporate sector, especially in manufacturing, logistics, e-commerce, technology and construction, have openly supported the reforms. They emphasise that India cannot aspire to be a major global supply-chain hub without modern labour laws.

On the downside, the codes weaken job security in sectors where permanent employment was already shrinking. The shift in wage composition may lower take-home pay for millions of employees even though long-term social security contributions increase. Critics say the codes focus too heavily on ease of doing business rather than ease of living for workers.

Government’s Reasoning and Reform Logic

The government argues that India’s labour law structure was rigid, outdated and discouraging to employers. It has repeatedly said that excessive compliance burden pushed companies to remain small, avoid formal hiring and rely on contractual labour. By consolidating 29 laws into four, simplifying definitions and adopting digital compliance, the government believes it is facilitating growth, formalisation and better coverage for workers in the long run.

Official reasoning also stresses the need for flexibility in a rapidly changing economy where global supply chains demand quick scaling and cost efficiency. According to the government, job creation will increase only when industries feel confident to expand without regulatory fear.

Despite parliamentary approval, complete implementation requires states to finalise their rules, and many have not. With unions demanding rollbacks and industries waiting for clarity, India’s biggest labour reform in decades sits at a crossroads. The codes promise modernisation and efficiency, but they also risk unsettling a workforce already anxious about job security. How these laws eventually take shape on the ground will depend on the balance that the government strikes between employer flexibility and worker protection.